When Royden Sanders’ professors at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) concluded that their student’s thesis was “too complicated,” like other later dropouts — Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, Ted Turner, Mark Zuckerberg — Sanders walked. And he went on to create even bigger and more complicated devices and operations, starting with one of his first military creations, the FM radio altimeter, advancing through what we now recognize as the tough but productive path of creativity. Sanders worked with Raytheon’s famous “Team of 11” to produce engineering firsts that took us into the moon race and beyond. And like so many entrepreneurs before him, in 1951, Sanders started what would become his biggest innovation in the Charles River Basin, a fertile crescent that spawned so many textile, automotive, machining and plastics firsts (see Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation). One year later, he moved the enterprise to the top two floors of yet another ancient brick mill, this one a former textile operation along the Nashua River, less than a mile upstream from the mighty Merrimac, the larger waterway that powered the Unites States’ first industrial revolution.

From Small Brick Mills to Bigger Brick Mills

The company that bore his name, Sanders Associates, continued to expand its portfolios until acquired by Lockheed and finally BAE Systems. A different kind of worker moved into the brick mill, replacing the mill girls and machine tenders of the dying textile and shoe shops. Sanders’ brick mill lay at the very edge of one of Nashua’s larger immigrant neighborhoods, French Hill, bounded on the south by the Nashua River and St. Francis Church, and the north by the city’s older, more gentile homes.

But even for well-funded and well-established innovation engines like Sanders Associates, getting from design to prototype to full production could take months of work, rework and some missed launch dates. For an industry that worked primarily in metals, casting and mold building and first production, multistep, precision processes sometimes produced unsatisfactory results. What Sanders required even in the earliest design and prototype stages was precision and predictability, the kind of exactness that centuries of metal-working technology could not always deliver.

And so Sanders returned to the lab to come up with yet another solution. Working from digital innovations, including inkjet and desktop printers, Sanders created an answer to lengthy and unpredictable prototype development. By then, well into his 70s at his new startup, Sanders Prototype in Wilton, NH, would speed up the design process by creating a three-dimensional prototype from a computer-aided design, i.e., hardware from software. Sanders Prototype produced the Model Maker Plotter System, a desktop unit that made models of small parts one layer at a time at a CAD workstation. Sanders’ new creation reduced time to market while it offered engineers a new tool to “see” and create small parts earlier in the cycle and on site. The first models sold for $70,000; they were initially used to produce small parts for the jewelry, automotive and aircraft industries. From a CAD system file, the machine deposited overlapping droplets of plastic “wax” material in layers two thousandth of an inch thick, creating an object that could be up to six inches in height, width and depth ready for molding or casting.

Early machines were delivered in up to 60 days. Fast-forward 20 years to 1994, when Sanders Prototype evolved into Solidscape Inc., based in Merrimack, NH.

“Solidscape, a Stratasys company, believes in innovation and offers more models and choices for a bigger range of possibilities — not just design-to-market rapid development, but a way to personalize and customize design,” said Dan McCarty, vice president of operations. “Customers can expect to receive their machines in weeks, sometimes days, thanks to the New Hampshire company’s workforce and lean sourcing and manufacturing improvements.”

According to Vice President of Marketing William Dahl, a high-tech veteran, industry applications for additive manufacturing technology are the exciting breakthroughs that have energized Solidscape. The machines have become more affordable, with prices ranging from $25,000 to $46,000; now smaller jewelry and medical equipment businesses, as well as educational institutions, can afford the technology.

In the global jewelry business, for example, where more customer input is now part of the design process, these magical devices have taken off. Not only do designers want to capture a consumer’s design ideas through online offerings, they want to display design results immediately, without repeated trips back and forth to artisans’ studios. Like in many other industries, artisans are fewer, and 3D precision modeling machines offer an alternative.

Lisa Krikawa of Krikawa Designs recalled how the company’s first machine changed its business. “This is a transitional time for my company; we are looking at new designs and new techniques to integrate into the workshop,” Krikawa said. “We are on the threshold of creating a new line and couldn’t do it without it.”

Another jeweler, Harry Shahbazyan of Ani Jewelers, echoed the technology advantages. “If you look at the business side of it, price per ring to print, I don’t care which other company is out there, Solidscape is less,” Shahbazyan said. “Ani has tripled its output compared to traditional methods.”

Other technology applications include patterns for investment casting and mold making in dental labs, turbine blades, biomedical products, orthopedics, consumer goods, electronics and toys. Small dental labs that outsourced precision dental work offshore are finding that they can bring the business back home. One small dental lab owner cites his new work flow, speed and precision as competitive advantages offered with this technology.

Russ Binder believes that his lab can compete with China because he can do more in-house. “It starts to feel like you’re adding and subtracting wax like you used to … but you don’t have to carve it. … That enhances … production and enhances your brand,” Binder said.

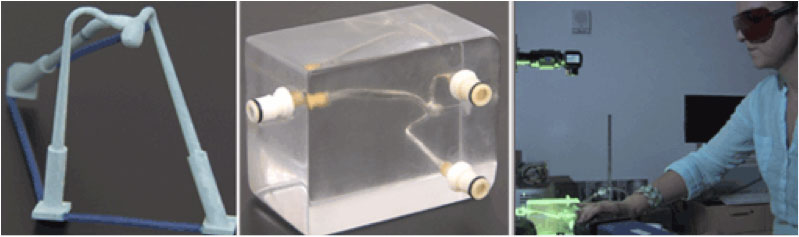

Taking design and casting solutions one step farther in medical research is Dr. David H. Frakes, principal investigator at the Image Processing Applications Laboratory at Arizona State University, where scientists using 3D technology are exploring the impact of brain aneurysms. By building core blood vessel models, Dr. Frakes’ team can then translate them into transparent flow models that become exact replicas of a deadly cerebral aneurysm. By simulating various positions and conditions, the researchers can use advanced image processing to predict and isolate what-ifs.

Bringing manufacturing back to the innovation zones where breakthrough ideas were born is exciting. Who knew that less than a half mile from the Merrimac River that powered so much innovation in machine building, we would find another manufacturing pioneer expanding to offer new smart solutions for the historic molding and casting industries? Dahl said: “We continue to experience annual double-digit growth, and we have introduced more new 3D printer products in the past 14 months than in the previous six years.”

Nearly 85 percent of Solidscape’s workforce is either in engineering and new product development or manufacturing operations and service. All product development, including design, hardware, software and materials, is done in Merrimack. Likewise, all manufacturing of hardware, software and printer materials (waxes) is also done in Merrimack. “We have never received government funding support, and we are a good, old-fashioned, boot-strap ‘Made-in-America’ story. We take great pride in our local path to a global footprint,” Dahl said.

Although Solidscape’s employees number 62 in Merrimack, with 55 global partners supporting more than 4,000 Solidscape 3D printers in 80 countries, McCarthy is starting to feel growth pains as he tackles lean manufacturing and sourcing challenges in the midst of business expansion. It’s a great problem to have!

Named by Fortune magazine a "Pioneering Woman in Manufacturing," Patricia E. Moody, The Mill Girl at Blue Heron Journal, tricia@patriciaemoody.com, is a business visionary, author of 14 business books and hundreds of features. A manufacturing and supply management consultant for more than 30 years, her client list includes Fortune 100 companies as well as start-ups. She is the publisher of Blue Heron Journal, where she created the Made In The Americas (sm), the Education for Innovation (sm) and the Paging Dr. Lean series. Her next book about the future of manufacturing is The Third Industrial Revolution. Copyright Patricia E. Moody 2013. All rights reserved.