How Zingerman’s accelerates flow through an improved tool mix and employee engagement

If you’ve tried it all—Kanban, standard work, coaching—the works—and experienced uneven progress plus poor sustainability of your company’s performance gains, the Zingerman’s Mail Order story can offer lessons learned about how being open to new methodologies and ways of working together is necessary to continuous improvement.

Critical to this more-successful approach: a combination of embracing more effective improvement tools and believing in people. In addition to introducing new tools, managers at Zingerman’s have learned to coach and encourage employees to develop and execute improvement initiatives. The benefits reaped from this hard-won transition, Zingerman’s leaders say, is faster and more accurate order fill rates required by its seasonal business.

This mindset change did not take place overnight, or easily. The journey to date has lasted more than 15 years, during which the company applied several continuous improvement practices—including one that supported the success of the others: Toyota Kata. Here’s how people at the company, also known as Zingerman’s Community of Businesses (ZCoB), progressed so far, adding new strategies along the way.

Recognizing the need for change

A primary challenge Zingerman’s faced: Roughly 50 percent of sales occur during the winter holiday season, handled by a workforce that swells from 70 to more than 300 during that period. “We traditionally did batch fulfillment, creating gift boxes ahead of orders, guessing at demand,” said J AtLee, a production manager at the Ann Arbor, Michigan-based company. “We would build a ton of gift boxes and hope that we had the right number—and also hope that we could remember where we put things. Ten months of the year that went pretty well.”

During the holidays, however, frustration and time wasted on identifying what was in pre-packed boxes (artisanal cheeses, bread and other items) mounted. “We had no labels indicating what was in gift boxes that were stacked on pallets,” AtLee said. The company relocated the business four times, each time to a larger location, with the mistaken hope that operations would somehow become more efficient.

Lean beginnings

Zingerman’s got its first taste of lean concepts with the arrival of Eduardo Landers, a student at the University of Michigan, in 2003. Now a consultant for the business, Landers was scouting for dissertation material on lean practices. Part of this research focused on mail-order operations and variables such as seasonality, numerous SKUs, perishability and other factors. Zingerman’s three warehouse managers began meeting with Landers during his site visits. Over time, company leadership evaluated the company’s “current state” and lean strategies, eventually deciding that lean was the way to improve operations.

“The first lean tool we implemented, or tried to implement, was Kanban,” AtLee said. “We created ‘markets’ where we picked orders, creating routes to replenish those markets.” This strategy was less successful than expected. Noting the lack of widespread engagement in the new process, AtLee said, “The bottom line is, improvements were pushed by managers. We made some progress, but the effort was extremely high, and the payoff and sustainability were low.”

Trying another tactic, then a few more

After pull markets were in place, the company added another tactic to its mix of methodologies: Just In Time (JIT). “We only made gift baskets to order,” AtLee recalled. “Yet as managers, we were not entirely convinced that this would be successful. We thought it was a good idea, but we had concern about not being able to complete all the planned work on a shift.”

Once again, a new approach brought unexpected hitches. “We learned that JIT doesn’t necessarily eliminate issues, but it exposes them,” said AtLee. “As we eliminated built-up inventory, we could see where our processes failed us. Inventory had been used as a Band- Aid® for processes that could not keep up with demand.” While JIT enabled managers to discover new issues to address, it did not offer relief from them as expected.

Employees developed a skill test for potential new associates (the test is “in progress” in this photo). It is an example of staff-driven improvements to the hiring process.”

Managers then explored and trained associates—using TWI (Training Within Industry)—to identify and implement standard work. Building on what they learned implementing earlier tools, they understood the importance of gaining employee buy-in. Using TWI to teach employees how to create standard work in their own work area helped increase employee acceptance of the practice.

“We needed a starting point, and then we could break down process steps to see what could be eliminated or combined,” AtLee said about this strategy. “We knew crew buy-in was necessary, so they would ‘own’ their work area (and processes). We talked with them about creating standard work descriptions— SOPs, or standard operating procedures—and we told people, ‘Go!’” Once the employees had created standard work, they set about improving work processes. For example, core team members began releasing orders at takt or a set pace.

Amid the success, however, the Zingerman’s team again discovered a new problem. “People didn’t fully understand this approach at first, so it was kind of herky-jerky,” said AtLee, adding as an example: “We used to create packing slips for the day without knowing how long it would actually take to get through everything.

“So, we started ‘help your neighbor’—people went to where the bottlenecks were, and then returned to their regular places,” AtLee said. “We also started tracking takt to gain increased process visibility. Later, we began sequencing orders to handle order flow.” Orders were printed throughout the day, with same-day orders accepted until 3 p.m. A portion of the orders were picked and packed early in a shift. Workers had to assemble and fulfill other orders as they arrived that day. The new processes worked with one exception: If a sale advertisement went out and orders for a newly promoted product spiked, pickers struggled to keep up with demand. To address this issue, the company deployed new programming for the order-taking system, which provided increased visibility on batches of orders, indicating where pickers should concentrate their efforts.

Still more new practices

Managers then targeted one-piece flow. Again, uneven progress toward this goal prompted managers to evaluate factors getting in the way. “We had concentrated on printing orders and picking when we needed to look further downstream, pushing waste out,” AtLee said.

The company also adopted daily huddles on the line and a relatively flat hierarchy but found those practices did not compensate for inadequate training. “We now realize that we need to help people in learning new skills,” said AtLee. “We talked about expectations, but change doesn’t happen that way. For years, we had expected people to do a visual representation of what went on in a station—run charts, etc. We thought we were coaching, but we spent more time training people on Excel, PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act), etc. What we needed was to learn how to get people more involved.”

Managers recognized that they had equated training employees about PDCA, takt times and other lean basics with effective coaching. “Our words were not matching our actions, when we thought we were empowering people,” AtLee said. “We slowly learned how to let go and let people drive change. We had obstacles to that transition, caused by the way we were taught to manage.”

Enter Toyota Kata

Zingerman’s leadership perspective began to pivot in 2013. Jeffrey Liker, a University of Michigan professor of industrial and operations engineering, visited Zingerman’s that year with industrial and operations engineering (IOE) student groups and then introduced AtLee and fellow managers to Mike Rother. Rother is a researcher and author known for promoting the concept and practice of Toyota Kata, a disciplined approach to developing—and helping employees develop—a scientific mindset that enables effective problem-solving.

“We started discussing how we had concentrated on using a lot of tools,” AtLee said of conversations with Rother, Liker and IOE students (who conducted five onsite projects at Zingerman’s). “We talked about how Kata (improvement) is more about how we work and how we look at things—a mindset change. We started to learn what Kata is and what it isn’t. My perspective on what can be planned changed. All we can do is plan a step and then break it into bite-sized pieces that we work through in coaching cycles.” This scientific approach involves understanding the current challenge and the current condition, establishing the next target condition and experimenting with strategies for achieving the target condition.

Front-line employees drive engagement

With the introduction of Toyota Kata, people started to get excited about and involved in the Kata coaching cycles. Their enthusiasm for the practice transformed process improvement at the company: employees became more engaged and began driving improvements. “We asked ourselves why people liked this approach,” AtLee said.

Karen Shepard (left) points to a storyboard about pick mistakes during a coaching cycle with J AtLee.

Employees valued the opportunity to learn and use their brains. They were treated as content experts, and they relished the challenge of improving their processes.

“We started learning as learners and coaches all at the same time,” AtLee said. “Although it was uncomfortable and wobbly at first, working together in a different way, now it’s easier. Now, if someone asks a question about a process, I can say, ‘I don’t know; let’s find out together.’ It’s not about being managers, but about supporting our crew in finding out whether changes will work, and asking ourselves, ‘What did we learn?’”

For managers, this shift challenged traditional ways. “It was important to build relationships built on trust, deliberately supporting our crew in adopting a scientific method and not attempting to provide all the answers,” AtLee said. “We needed to provide guidelines and a safe environment for people to experiment. We needed to let experiments run their course, emphasizing the rigor of the process, not the outcome. This was an extremely difficult mindset for a manager and still is. Using this approach—day-to-day tryouts—in two years, we achieved more than we did in the previous 10 years.”

Improvement initiatives continue

Zingerman’s managers and employees continue working together to drive incremental improvements. An example: When internal mistakes such as order fulfillment accuracy occur, they’re tracked before they go out the door. As associates find such glitches, they take a few minutes to document what’s amiss in an order and then, with a core (year-round) crew member, participate in a coaching cycle. “It takes only a few minutes to ask key questions and post improvement suggestions (and possible action items) on a board,” AtLee said.

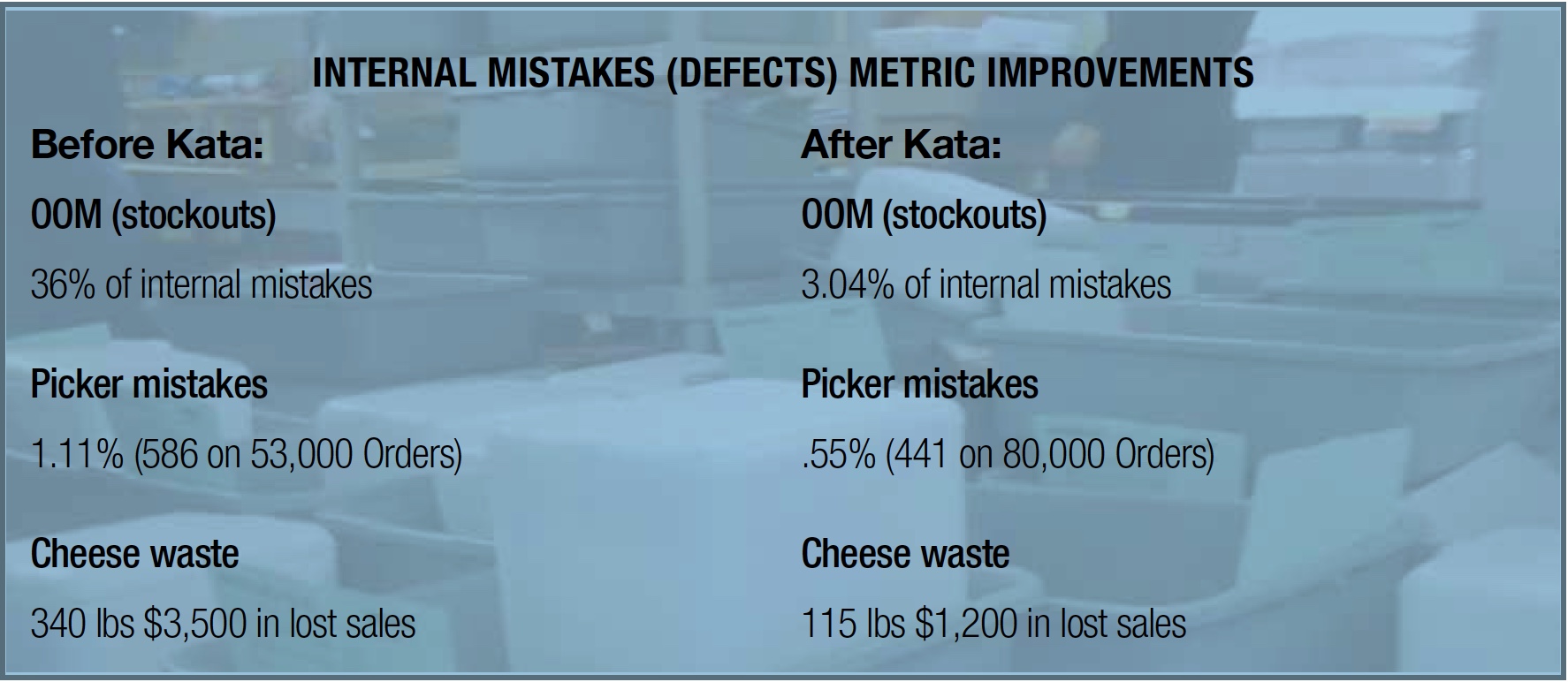

The success is notable. “When we started with coaching cycles, almost 1.25 percent of orders had mistakes. We worked with people, creating a storyboard and looking at what pieces of the process didn’t fit together. After a year and a half working on these issues, we moved to just above 0.5 percent of orders with mistakes, while our total sales volume increased.”

About Zingerman’s

Zingerman’s Mail order is part of Zingerman’s Community of Businesses (ZCoB), which is a community of 10 business units dedicated to providing full flavored, traditionally made artisanal foods (cheese, cakes, pies, breads, etc.). Sales: nearly $60 million. Three bottom lines: great food, great services and great finance. The company employs about 300 temps during the holidays and 70 regular employees (warehouse/fulfillment). http://zingermans.com.

Lea Tonkin is the owner of Lea Tonkin Communications in Woodstock, Illinois. This article originallay appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of Target magazine. For more information about Mike Rother’s Kata research, visit https://slideshare.net/mike734.