Following a recent workshop last June, Bill Robertson, the IT director at De Bortoli Wines Australia, made a seemingly off-hand comment that I think is a crucial insight about continuous improvement. As we discussed one of the projects he was leading, he said: “You know, we often lead change through projects in our organization, but about 10 percent of the change is technology based, the rest is people based.”

Robertson says it’s 90 percent about people, but here’s the problem: Most of our programs and methodology are 90 percent about the tools. Even lean and continuous improvement initiatives, which are fundamentally about solving problems and implementing change, too often get reduced to tools. So that begs the question: How do we prepare people—our workforce—to adapt to change?

Changing mindsets

Each of us has a mindset through which we see the world—our perceptions. In the image, at right, some of us will see the old lady (facing us), some of us the young lady (facing away), but we are all looking at the same picture.

Our mindset makes us pay attention to certain things and ignore others. It influences how we interpret what we see and hear. That is why there is often a difference between what is actually said and what the listener hears—this being the root cause of many a conflict and many continuous-improvement projects gone awry!

Our mindset makes us pay attention to certain things and ignore others. It influences how we interpret what we see and hear. That is why there is often a difference between what is actually said and what the listener hears—this being the root cause of many a conflict and many continuous-improvement projects gone awry!

Mindset can support agile behaviors or can hinder them. Any improvement exercise involves multiple people or groups working on different parts of the puzzle. How they understand customer needs and how they collaborate to create a cohesive whole can greatly influence success. Agile thinkers are aware that their own perceptions are shaping their view and that they must be wary of believing everything they think. Agile thinkers tolerate some ambiguity. To navigate that ambiguity, they experiment and continually test the views created by their perception. And from those experiments, they find the way forward, adapting as need be. This mindset is quite different from one where they are just following pre-defined actions in a project plan.

So, of course, the answer seems to be to teach people a better way of thinking and working. Tell them the better way and ask them to follow the methodology— easy.

Unfortunately, hoping to create new behaviors by explaining or trying to convince people doesn’t work. The explanation may be correct, but it doesn’t change the habitual ways of thinking that have built up over the years.

Practicing Toyota Kata

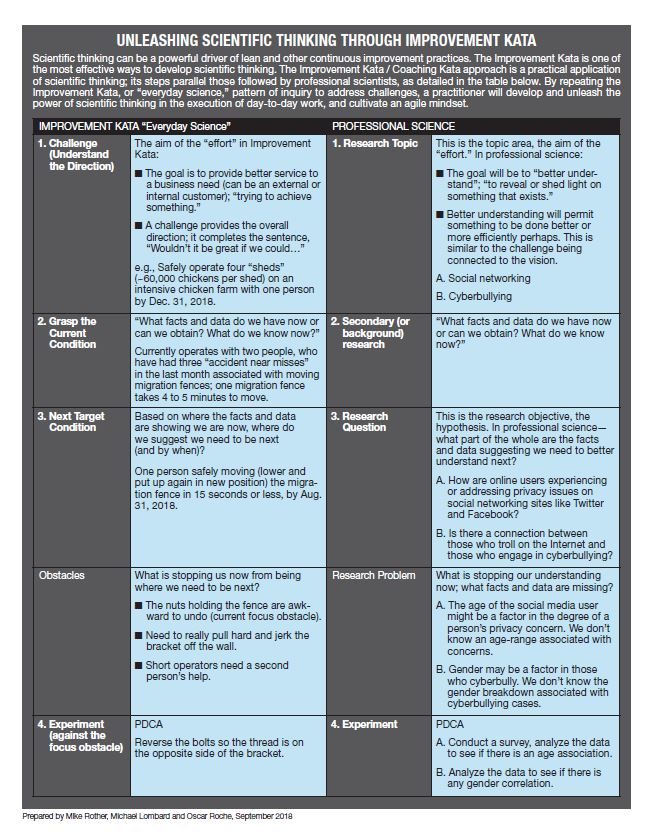

One answer that has arisen in recent years is deliberate practice of the so-called Improvement Kata (Mike Rother, 2009), one of two practices— patterns of thinking—that is part of Toyota Kata, a way of developing scientific-thinking skill and mindset in any team or organization. The core concept of the Improvement Kata is to learn a new way of thinking via practice with corrective feedback. This is a way of applying a greater scientific-thinking discipline to questions, then validating or disproving our perceptions—or our preconceived mindset. It is a means toward behaving in an agile manner.

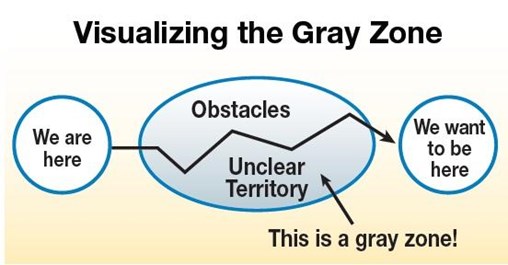

The Improvement Kata does not prescribe a step-by-step plan to achieve the target condition. This acknowledges that there is a gray zone where experiments need to be conducted to determine the next steps.

The Improvement Kata is a four-step pattern of deliberate practice that, as a whole, parallels scientific thinking:

Step 1 Sets a direction by defining a challenge or goal.

Step 2 Requires getting an understanding of the current situation. Where are we now?

Step 3 Establishes a next state—the next “target condition”—that is achievable soon, on the way to the bigger challenge. (Now a gap is clear.)

Step 4 Uses rapid experimentation to navigate toward the target condition. It’s not easy to adopt a new way of thinking. That’s why there is also the Coaching Kata to practice—a questioning pattern that helps anyone develop greater scientific thinking.

- What’s our target condition (the in-between state)?

- What’s the actual condition now? Now reflect: What did we learn from our last experiment?

- What obstacles are stopping us from reaching our target condition, and which one will we work on?

- What’s our next experiment?

- How quickly can we see what we’ve learned from that?

Practicing the Improvement Kata keeps we focused on where we need to be but doesn’t engineer a project plan approach to get there. Why? Because within the fourth step of the Improvement Kata, we don’t prescribe step-by-step how we think we can get there. We acknowledge there is a grey zone between where we are now and where we need to be.

The Improvement and Coaching Kata patterns give you a way to develop the 90 percent people-based process that Bill Robertson was referring to and achieve whatever you want. What a perfect fit for the dynamic, unpredictable conditions of the early 21st century.

Oscar Roche is a director of the TWI Institute Australia and New Zealand and an Institute Toyota Kata Master Trainer. Mike Rother and Jeffrey Liker provided writing assistance. This article originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of Target magazine. For more information about Kata, visit the AME Kata resources page.