“I feel like this is taking too long,” I cautiously told my new manager, Fred. “Aren’t they going to get impatient?”

“Worrying about that is my job,” Fred said firmly, with a gesture informing me that my visit to his office was over, “Your job is to focus on your experiment today.”

Two months earlier, I’d left my role as a quality engineer to learn lean under Fred. As part of my training, he had volunteered me to lead an effort to compress lead time in a struggling paperwork process. This process was forcing finished hardware to sit for weeks while IT completed the required documentation, causing late deliveries to the customer.

This was not a good look for a program attempting to wrap-up development and earn a long-term production contract, so these problems were getting a lot of attention. It was widely rumored that our company’s president had been summoned to the customer’s headquarters and verbally berated over the matter.

Seeing the potential for glory, I was eager to rise to the challenge and be the hero. Yet a month after starting work on this process, I had done nothing at all to improve it, and my enthusiasm was turning to anxiety over this lack of progress.

I had initially expected to facilitate a kaizen event, to gather stakeholders, build a list of problems and countermeasures, then drive the implementation plan. Turned out I was very wrong. Instead, I spent weeks following a scripted process analysis routine, conducting small exercises each day to deliberately observe and characterize the current state in great detail.

Between every exercise, I would carry a black trifold containing my “storyboard” to Fred’s office. There, I would face a coaching routine, where, through a series of scripted questions, Fred would examine my results and vet the plan for my next step. These discussions frequently revealed flaws in my work, often ending with Fred asking me to repeat the exercise based on what we had just learned. Sometimes this meant tediously iterating a piece of work multiple times over several days. Even more frustrating, any time that Fred perceived in our coaching sessions that I was being defensive about mistakes or making claims that weren’t supported by my facts and data, he would bluntly call out my behavior and turn the discussion to the flaws in my mindset.

Having been comfortable and well regarded in my quality role, it was tough to go through such a grueling experience in this new role. I felt inept and, for the first couple months, frequently doubted my decision to transfer. Along the way, I was consistently amazed by how unconcerned Fred seemed to be with our lack of progress in making improvements. He focused instead on tiny details in my work and thinking: Didn’t he realize how important and urgent this project was?

A couple weeks later, I took a two-week chunk of lead time out of the process. During my analysis, I had stumbled across a quirky detail in a time-consuming step of the process, realizing that this operation might be bypassed entirely simply by photocopying one particular sheet from each set of documents. Following a little negotiation with team members to test this idea and then implement it through some trivial changes, the paperwork flow improved dramatically.

Downstream team members loved the smoother flow of incoming paperwork, and leadership was pleased with the high-impact, no-cost result. My discomfort was only slightly eased, however, as the daily exercises and coaching continued.

Shifting paradigms

This was several years ago at the beginning of my journey with Toyota Kata. (I assume that readers have some awareness of Toyota Kata. For readers not aware of it, read “Becoming agile in a dynamic world,” Target magazine, Summer 2018, p. 18. See also, Mike Rother’s Toyota Kata website at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~mrother/Homepage.html.)

My experience with this approach to lean has proven to be tremendously valuable to me, both professionally and personally, and today I’m deeply grateful to Fred for his gift of a great start on that journey. It wasn’t easy and often wasn’t fun, but looking back now I see fundamental misconceptions in how I initially understood Kata and suspect that these were responsible for much of my angst.

Since that time, I have encountered or assisted a number of other people at the beginning of their Toyota Kata journey and have found that some of these misconceptions appear to be widespread. Despite the powerful advance in lean that it represents, I have seen more Kata efforts struggle than thrive. I suspect that some of the issues relate to how this approach is being understood and subsequently implemented by the people leading these efforts.

Like previous approaches to lean, Toyota Kata seeks to enable organizations to gain and sustain competitive advantage through a cultural aptitude for process improvement. Kata is built on many of the principles and concepts that have been central to lean for decades. However, I have found that Kata also contains elements that stand in direct contradiction to how many organizations actually approach their lean initiatives.

Toyota Kata represents an attempt to correct various failure modes that are believed to have hindered lean initiatives in the past. It does so by refining our understanding of what has made Toyota so successful. By revealing this new understanding, I believe Kata essentially forces us to adopt a complete paradigm shift in how we approach process improvement.

Practice, practice, practice

The essence of this paradigm shift crystallized for me this past spring. As his long hockey season finally drew to a close, my wife and I gave our 7-year-old son some outdoor options on how to spend his extracurricular time over the next few months. He decided that he wanted to learn to play baseball, so we signed him up for our town’s Instructional League.

I’ll try to say this diplomatically: The first several games were full of effort but less than captivating to watch. By design, every single play was a throw to first base—inning after inning. There were no outs, no score kept, no balls and strikes. Just the exact same pattern with each batter: Coach pitches and batter swings until a ball is put in play, defender throws the ball to first base, batter is safe at first and all runners advance. This was the same pattern used for practices, meaning that the only difference in “games” was that the kids were proudly wearing their uniforms and excited to be facing an opposing team.

Still, parents filled the stands at each game, and we enjoyed being there. We all understood that this wasn’t about watching a great ballgame or seeing amazing skills on display. It was about enjoying the moment while making progress toward something down the road. Our kids were having fun and working hard, and they were getting better.

As the weeks passed, the games began to move faster, with fewer awkward at-bats where a kid would struggle through 20 pitches before finally squibbing a ball close enough to fair territory that the coach would send him running to first. Fewer balls rolled to a stop on the infield dirt after eluding three or four fielders. A popup might be caught on the fly. More hits were driven far enough to land in the outfield grass. More throws to first base made it to the first baseman—and were caught. The skill growth over two months was remarkable.

Toward the end of the short season, it struck me that Toyota Kata and the Instructional League were essentially doing the same thing. Each is fundamentally a means of skill development, putting learners through frequent practice of structured routines to help them grow certain desired capabilities. Whereas the Instructional League seeks to ingrain foundational skills needed for successfully competing in baseball games down the road, Toyota Kata seeks to ingrain the foundational skills in scientific thinking needed for consistently driving process improvement aligned with business strategy. In both settings, initial awkwardness and ineptitude are not just tolerable—they’re normal. Showing up every day and practicing hard is the expectation.

The difference is in how

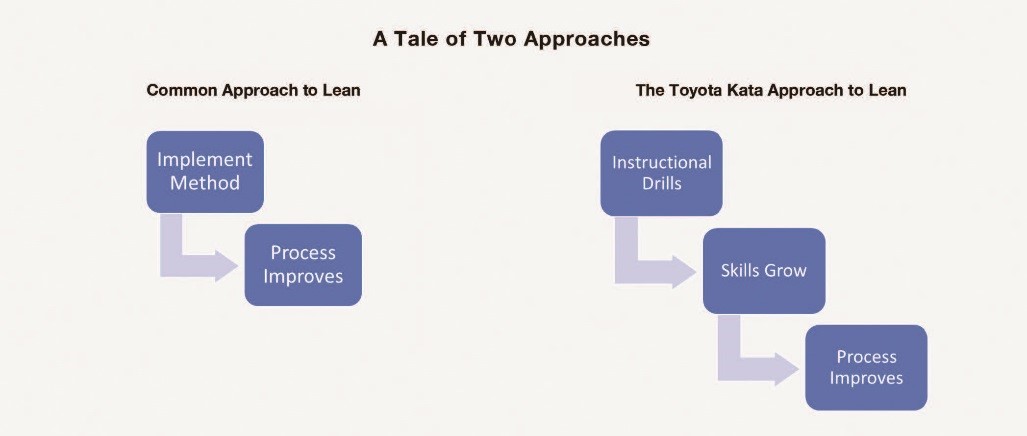

This primacy of skill development—where correct, consistent practice is initially more important than process improvement results—is something I completely missed when I first started working with Toyota Kata.

When I was baffled by Fred’s apparent indifference to the lack of process-improvement results and frustrated by his seeming fixation with my mindset, I was failing to see that he was simply focused on helping me correctly practice the Improvement Kata. It wasn’t that he didn’t care about our results, but that he knew results would follow if my skill grew. If he let me see him wringing his hands over poor results, what could that do besides undermine my practice? Finally, his long-term goal was to grow me into a lean practitioner able to help him teach Toyota Kata to others—so his greatest need was for me to grow a deep understanding of Toyota Kata’s mechanics and intent. Fred knew exactly what he was doing.

Critical Differences Between Lean and Toyota Kata

In the years since then, I’ve encountered many others who seem to have an interpretation of Kata similar to mine, taking its structured routines (i.e., the Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata) as methods to implement for process improvement. This makes sense—they’ve learned other powerful process-improvement methods such as kanban or poka yoke or batch-size reduction, and the Improvement and Coaching Kata fit nicely as shiny new tools in this toolbox.

The problem with this interpretation is that it perpetuates existing tendencies to chase process improvements rather hastily, lacking the critical element of struggling through deliberate practice needed to produce skill growth. That element is central to the Toyota Kata paradigm, and I believe that without it the door remains open to lean’s historical failure modes.

Management must make a leap

I have come to see Toyota Kata as conflicting with how lean is commonly approached in organizations, even though it really doesn’t change what lean is all about. For years, lean experts have emphasized the importance of coaching and skill development—exactly what Toyota Kata seeks. However, those aspects seem anemic in the dozens of lean initiatives I’ve encountered, where skill development is generally little more than awareness gained from a workshop (and perhaps a lightweight project) and coaching is at best infrequent and unstructured.

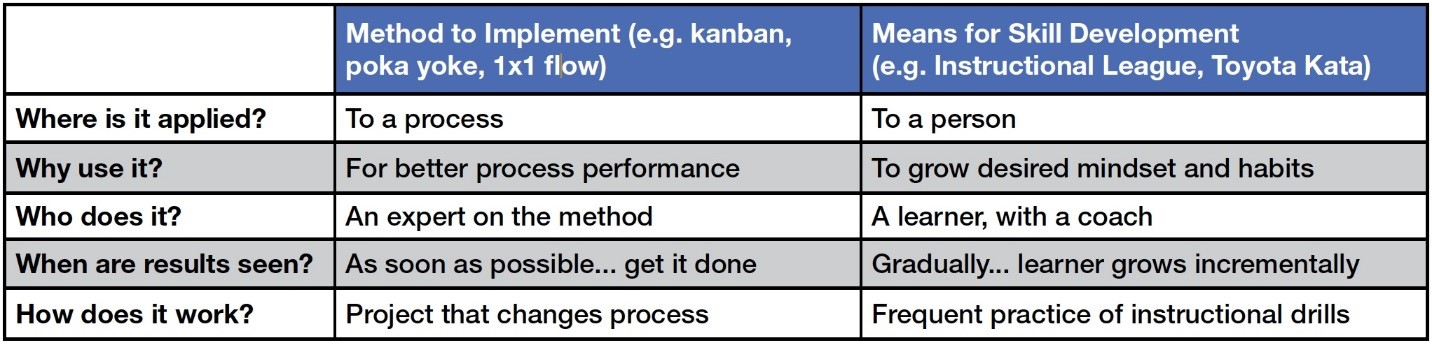

Toyota Kata adds value to the lean movement by defining a means of skill development that operationalizes these often-neglected principles with rigorous structure, even including an elegant approach to deployment. However, it seems that the fundamental concept of a “means of skill development” is foreign to the prevailing management paradigm in most organizations, which take lean to be a collection of “methods to implement.” For a Toyota Kata deployment to thrive and achieve its intent, I suspect that an organization’s management must see the difference between these approaches and embrace the goal of deploying a means of skill development.

Setting-up an Instructional League

I suggest that the task of leaders trying to deploy Toyota Kata parallels that of the directors who ran my son’s baseball league. A lot of work had to be done before practice could even start. Practice fields needed to be identified. Players and coaches needed to be recruited—and the latter had better be endowed with no small amount of patience (thanks, Fred). A schedule for practice and games needed to be produced, then modified whenever the unexpected occurred during the season (e.g., snow in mid-April). The league needed to have a mechanism for communicating news to participants, and for directors to meet periodically during the season to reflect on happenings and make adjustments.

All of these tasks have parallels in Toyota Kata, with the additional burden of the hard expectation that the deployment produce impressive process improvement results. This gives the leaders of a Toyota Kata deployment the fundamental responsibility of closely monitoring progress toward improvement goals as participants continue with their practice. If progress is lacking over time, the deployment’s leaders must react by making whatever adjustments in practice or coaching that seem appropriate.

Those leading a Toyota Kata deployment may find the work more challenging than the familiar approach to lean. It’s tough to rely on others to struggle and grow, when just doing it yourself feels faster with more reliable results. That said, I have found that the Kata approach ultimately offers far greater rewards for all involved.

Advice on starting a Toyota Kata ‘instructional league’

Here is some advice, based on the lessons I’ve learned, on how you can achieve a successful Toyota Kata deployment:

- Find processes that look like good practice fields, where the improvement challenges are meaningful to participants and the Process Analysis Kata is fairly straight-forward to apply, so that learners are likely to enjoy success from their early efforts.

- Communicate openly with coaches and learners that this is about building their skills and shifting their mindsets, and that they will be asked to persevere through initial awkwardness and ineptitude—as is normal in skill building. Remember: People seem most willing to try new things when senior leaders go first!

- For participants whose managers are not directly involved in Kata practice, ensure that those managers understand the skill development approach and agree to support it.

- Ensure that participants have a solid baseline awareness of Kata’s intent and mechanics before starting practice, so that correct practice of the routines will be possible.

- Establish Coach-Learner relationships where mistakes can be made safely and corrective feedback will be valued.

- Don’t ask people to practice where effective coaching is unavailable, because then people naturally just practice their existing habits!

- Find a way to ensure that practice sessions are happening frequently—ideally daily—and that the improvement and coaching skill patterns are being practiced correctly.

- Gauge whether proficiency with these skills is growing by watching the degree of actual process improvement, then adapt accordingly.

Tyson Ortiz is a Boston-based performance-improvement consultant. This article originally appeared in the Winter 2018 edition of Target magazine. If you're an AME member, visit the Kata Practitioner Community on the AME Networking site.